- Home

- Barry Callaghan

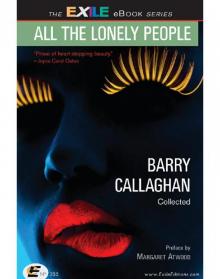

All the Lonely People

All the Lonely People Read online

Formatting note:

In the electronic versions of this book blank pages that appear in the paperback have been removed.

ALL THE LONELY PEOPLE

Collected Stories

BARRY CALLAGHAN

PREFACE BY

MARGARET ATWOOD

Publishers of Singular Fiction, Poetry, Nonfiction, Translation, Drama and Graphic Books

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Callaghan, Barry, 1937-

[Short stories. Selections]

All the lonely people : collected stories / Barry Callaghan ;

preface by Margaret Atwood.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-55096-790-6 (hardcover).--ISBN 978-1-55096-791-3 (EPUB).

--ISBN 978-1-55096-792-0 (Kindle).--ISBN 978-1-55096-793-7 (PDF)

I. Atwood, Margaret, 1939-, writer of preface II. Title.

PS8555.A49A6 2018 C813'.54 C2017-905877-0 / C2017-905878-9

Copyright © Barry Callaghan, 2018

Text and cover design by Michael Callaghan; cover photo Shutterstock

Publisher’s note: These stories are works of fiction.

Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product

of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

eBook publication copyright © Exile Editions Limited, 2018. All rights reserved.

ePUB, Kindle and PDF versions by Melissa Campos Mendivil.

Published by Exile Editions

144483 Southgate Road 14

Holstein, Ontario, N0G 2A0, Canada

www.ExileEditions.com

We gratefully acknowledge the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Ontario Media Development Corporation for their support toward our publishing activities.

Exile Editions eBooks are for personal use of the original buyer only. You may not modify, transmit, publish, participate in the transfer or sale of, reproduce, create derivative works from, distribute, perform, display, or in any way exploit, any of the content of this eBook, in whole or in part, without the expressed written consent of the publisher; to do so is an infringement of the copyright and other intellectual property laws. Any inquiries regarding publication rights, translation rights, or film rights –or if you consider this version to be a pirated copy – please contact us via e-mail at: [email protected]

For Claire, my Crazy Jane,

Who, at 83, left me too soon.

“What can you do

With such a crazy dame?

She knew, she knew.”

—HAYDEN CARRUTH

All the Lonely People

Full Disclosure Preface by Margaret Atwood

Because Y Is a Crooked Letter

The Black Queen

Without Shame

Piano Play

Our Thirteenth Summer

T-Bone and Elise

Intrusions

Between Trains

Dreambook for a Sniper

Déjà Vu

Crow Jane’s Blues

All the Lonely People

Dog Days of Love

Drei Alter Kockers

Third Pew to the Left

The Harder They Come

Buddies in Bad Times

And So to Bed

Anybody Home?

Poodles John

Dark Laughter

A Terrible Discontent

The Cohen in Cowan

Prowlers

Mellow Yellow

The Muscle

A Drawn Blind

Mermaid

Everybody Wants to Go to Heaven

Willard and Kate

A Kiss Is Still a Kiss

The State of the Union

Silent Music

Communion

Up Up and Away with Elmer Sadine

Paul Valery’s Shoe

FULL DISCLOSURE

Preface by Margaret Atwood

Barry Callaghan has been a friend since the early 1980s when we both lived in Victorian red-brick row houses in downtown Toronto, near the Art Gallery of Toronto on one side and, on the other, a number of Chinese groceries and garment wholesalers and Grossman’s Tavern and the recently closed Victory Burlesque. That’s a good frame for Barry’s work: his interests as a writer have been mostly urban, with one foot in high art and the other in the hustle and fight-for-your-place world on the fringes.

Our cat used to pretend to be a stray in order to mooch food from Barry and his beloved, the painter Claire Wilks. The same cat used to leap from rooftop to rooftop wearing a bonnet and a pinafore. Did he ever appear at the Callaghan/Wilks back door in full dress? If so, that would have been appropriate: Barry Callaghan has never shied away from a touch of the real-life surreal.

Barry and I are of an age – he was born in 1937, I in 1939 – and thus we both remember a time when the sides in street fights among groups of boys in Toronto were more likely to be divided by religion than by any other consideration. Toronto in the Forties and Fifties was a small, provincial, Protestant-dominated, blue-law city – blue laws governed such things as who could be seen drinking what, where, and when. Catholics – especially those of Irish descent – were somewhat of an out-group. In the boy wars, snowballs with rocks in them were hurled, epithets were shouted, fisticuffs exchanged, turfs defended.

Barry was unavoidably a part of that scene. But he also had a well-known writer for a father: Morley Callaghan had seen much of the literary world, such as Paris, and he’d published in places that were not Canada, such as New York. He wasn’t above knocking people down, such as Hemingway, in their famous boxing match. Powerful lessons for a growing boy: you could have the Art Gallery on one side of your personality tool kit, and the pugnacious, tinsel-bestrewn scuffle on the other.

Barry came of age with the sense that there was a party going on somewhere – probably among the haute-Wasps – to which his ilk would not be invited. So what? Throw your own party and make it better. In retrospect it seems no accident that the magazine he founded in 1972 was named Exile: a space for those excluded from the party. (There wasn’t ever that kind of monolithic literary party in Toronto, which has typically specialized in sub-groups; or if there was, I wasn’t invited to it either. But that’s beside the point.)

Here is a Barry Callaghan moment. When it came time for Morley Callaghan’s funeral, Barry tried to talk the officiants into some Dixieland jazz, because Morley had loved that music. They were having none of it. The service proceeded as usual, with speeches and prayers and boy sopranos, but when the coffin was being wheeled down the aisle, up from the choir loft rose a full Dixieland band, which burst into full throttle. That’s when the mourners cried.

Morley never would have pulled a caper like that. Barry did.

As a young man, Barry became, first, a reporter – sent forth to see, to report, and – newspapers being what they were – to cover usually the bad news. But then he morphed into a poet and fiction writer – a writer of short stories, for the most part.

Barry Callaghan was never fashionable. He was never merely clever or witty. He was never “post-modern.” He was always off to the side somewhere, pursuing an aesthetic of his own that was not that of the prevailing zeitgeist.

How to convey the flavour of his prose?

You might divide prose styles into the Plainsong – such as Hemingway’s In Our Time – and the Baroque, such as Faulker or Proust or Thomas Wolfe. For Plainsong writers, less is more. For Baroque writers more is more, and the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom. Callaghan inclines to the Baroque.

He has never been interested in other people’s ideas of good taste. A pie in the fa

ce for it, and a knuckle sandwich into the bargain! Beige is not his colour. If he were a parade it would be a Mardi Gras parade. If he were a church it would be a Mexican cathedral, and the more candles and paper flowers and gold ornaments, the better. If he were a musical entertainment, it might be Gypsy – there’s no business like show business, and when in doubt take off your clothes, but not quite all of them. If he were another writer, it might be Dashiell Hammett crossed with a Jacobean playwright. If he were a sideshow attraction… Will it be the Bearded Lady or the Siamese Twins Joined at the Head, or will it be the carnie who lures you with the offer of winning a Kewpie doll, and, when you lose, gives you one anyway?

And what sort of dessert would he be? Not the plain apple. There would be whipped cream in it, and booze. It would be rich.

His characters have emotions, and they have them all over the page. People cry, including men. People are sentimental and sorrowful and enraged and in love and in lust, as people are. People drink. People wallow in misery and bask in pleasure. People fail. People fall apart. Life is not tidy. Approaching a Callaghan story, it does no good to stick a toe in.

Here you are. Plunge in!

I

Everybody wants to laugh,

Nobody wants to cry,

Everybody wants to hear the truth,

But still they want to lie.

Everybody wants to know the reason

Without even asking why.

Everybody wants to go to heaven,

But nobody wants to die.

—ALBERT KING

BECAUSE Y IS A CROOKED LETTER

…a motiveless malignancy…

—JOHN MILTON, Paradise Lost

THERE’S A HOLE IN THE BOTTOM OF THE SEA

It began over a year ago. I was going to drive to the foothill town of Saratoga to stay for two weeks in a rambling, spacious house and try to have lunch every day at a table under the tent at the old gabled racetrack. I had renegotiated the mortgage on the house and bought a new pair of tinted prescription sunglasses so that I could read the racing form in the glaring sun. C. Jane had packed several oblong dark bars of wax and her slender steel tools. She is a sculptor. I am a poet. We went out the back door of our house, through the vine-covered and enclosed cobblestone courtyard, and decided to move the car forward in the garage, toward the lane. I turned the key and the Audi lurched backward, breaking down the stuccoed wall, dumping concrete blocks and cement into the garden. I looked back through the rear-view mirror into an emptiness, wondering where everything had gone, and I heard the whisper of malevolence and affliction on the air. I did not heed it.

The car was fixed. Mechanics said that wires had crossed in the circuitry. We drove to Saratoga where every morning in the lush garden behind the house I wrote these words while sitting in the shade of a monkey puzzle tree:

pain and pleasure are two bells,

if one sounds the other knells.

The house was a brisk walk from the racetrack where shortly after noon grooms started saddling the horses under tall spreading plane trees, and then they led the horses into the walking ring and people pushed against the white rail fence around the ring, the air heavy with humidity. Some horses, dripping wet, looked washed out, with no alertness in the eyes. It is a sign, but it is hard to know if a horse is sweating because of taut nerves or heat, so I looked for the blind man.

I stood against the rail along the shoot from the walking ring, at a crossing where the horses clopped over hard clay. The blind man came every season on the arm of a moon-faced friend, and they always held close to the rail as the horses crossed, the blind man listening to the sound the hooves made. “Three,” he said at last, “the three horse.” The horse was dripping wet from the belly but I went to the window and bet on the blind man. The horse got caught in the gate, reared, and ran dead last. A warning, I thought, but before the next race the blind man said sternly to his friend, “I can’t close my eyes to what I see.” I moved closer to him. The other horses he heard during the day ran well. He called four winners and I strolled home to the big house and C. Jane and I drank a bottle of Château Margaux, 1983, a very good year. A few more winners and I might be able to pay for our trip.

That night I dreamed of butterflies swirling out of the sky and clouding the track. “It’s all our lost souls,” C. Jane said. The days passed. I worked on poems in the morning and forgot the blind man and the butterflies. I wrote about my dead mother, who would sit in candlelight, her sleeves stained by wax, and play the shadows of her hands like charred wings on the wall.

The sun shone but did not glare. I did well at the track and bought a Panama hat.

One morning, the phone rang and it was C. Jane. She had driven through town along the elm-shaded side streets. There had been an accident. When I got to the intersection I found our Audi had been T-boned by an elderly man from California who was driving a Budget rental car. “I was listening to Benny Goodman on the radio,” the man said, “Sing, Sing, Sing. It still sounds great.” He had gone through a red light, slamming the Audi up over a sidewalk and onto a lawn, smashing it into a steel fence. Marina had stepped from the car unscathed but stricken. The car’s frame was bent and twisted and it was towed to a scrapyard where it was cannibalized and then reduced to a cube of crushed steel. There was a whisper of malevolence and affliction on the air but I did not heed it and we went back to our home in Toronto where I was cheerfully sardonic about the hole in our garden wall. “There’s a hole in the bottom of the sea, too,” I said, and laughed and then began to sing, There’s a hole, there’s a hole in the bottom of the sea…

LIKE MY BACK AIN’T GOT NO BONE

Our house was in Chinatown, a red-brick row house built about 1880 for Irish immigrants. It had always been open to writers who dropped in on us for a morning coffee, and a little cognac in their coffee; sometimes I made pasta or a tourtière for two or three editors; and since C. Jane was a splendid cook, we had small suppers for poets from abroad and often we held house parties, inviting forty or fifty people. It was a friendly house, the walls hung with paintings, drawings, tapestries – all our travels and some turbulence nicely framed – but one Sept-ember afternoon the front door opened and a young man with bleached hair spritzed like blond barbed wire walked boldly in, his eyes bleary, and one shirt sleeve torn. He stared sullenly at the walls, spun around, and walked out without a word. C. Jane was upset. She began to shake and I felt a twinge, a warning, but I was too absorbed in getting ready to give readings in Rome, Zagreb, and Beograd, and then I was to go on to Moscow and St. Petersburg before coming home in late November for an exhibition of C. Jane’s sculpture. We decided to relax before I went away by celebrating Thanksgiving at the family farm near a town called Conn.

We loaded food hampers onto the back seat of our new Audi parked in the lane (C. Jane’s car was in the garage). I looked back through the broken wall, through the jagged hole. There had been no time to cement the blocks back into place. I felt a vulnerability, as if in the midst of my well-being, I’d forgotten to protect myself. Before she died, my mother had warned me, “People who buy on time, die on time, and time’s too short.” I checked the deadbolts and locks on the house doors. An old, fat Chinese woman waddled along the lane watching me with a stolid impassivity that made me resentful. She was my neighbour but I knew she didn’t care what happened to me. As she passed, I felt a sudden dread, a certainty that she belonged there in the lane, between the houses, and I didn’t. I remembered that my father, whenever he felt cornered like I suddenly felt cornered in my own mind, used to sing:

rock me baby,

rock me baby like my back

ain’t got no bone

roll me baby,

roll me baby like you roll

your wagon wheel home

THE QUEEN FALLS OFF HER MOOSE

Our farmhouse was on a high hill surrounded by birch and poplar and black walnut woods. The back windows of the house looked over a wetland, a long slate-coloured pond full o

f stumps and fallen trunks lying between gravelly mounds. The trees on the hills were red and ochre. There were geese on the pond. At dusk, we ate supper in the dining room that had old stained-glass church windows set into two of the walls, sitting under a candelabra that burned sixteen candles. “I think there’s a song about sixteen candles,” C. Jane said. “Or no, maybe it’s sixteen tons, about dying miners, or coal, or something like that.” For some reason, we talked about violence, whether it was gratuitous, or in the genes, or acquired, and whether there actually was something called malevolence, evil. I read something I’d written that morning to C. Jane: I love darkness that doesn’t disappear as I wake again but leaps a distance, unseen, and then as the sun sets, draws near. I see someone approaching: emerging from the dark, merging into the dark again. I smoked a pipe and we listened to Messiaen, Trois Petites Liturgies de la Présence Divine, and then we went to bed. I lay awake for a long while hearing the night wind in the eaves and a small animal that seemed to be running up and down the east slope of the roof.

In the very early morning, the phone rang. It was a neighbour from the city, a painter who had made his name by painting portraits of the portly Queen wearing epaulettes and seated sidesaddle on a moose. He was a shrewd, measured, ironic man, but he sounded incoherent, as if he were weeping. “Come home,” he said. “Come home, something terrible, the house, it’s been broken, come home.” I phoned our home. A policeman answered. “Yes,” he said, “you should come home, and be prepared. There has been a fire. This is bad.” For some reason, as we drove through Conn, I started hearing in my mind’s ear Lee Wiley singing over and over: I got it bad and that ain’t good, I got it bad…

A DREAMBOOK FOR OUR TIME

We pulled into the lane behind our house (after two tight-lipped hours on the road). I felt a terrible swelling ache in my throat: there, alone and in pairs and slumped in sadness, were many of our friends. What were our friends doing there? They came closer and then shied away, as animals shy from the dead. The police were surprised. They were expecting C. Jane’s red car (it was gone from the garage), and at first they did not know who I was, but then a detective took me aside. “You should get ready before you go in… I don’t know if your wife should go in, it’s the worst we’ve ever seen.” I looked through the gaping hole in the garage wall. “She’s not my wife,” I said. “We’ve lived together for twenty years.”

All the Lonely People

All the Lonely People